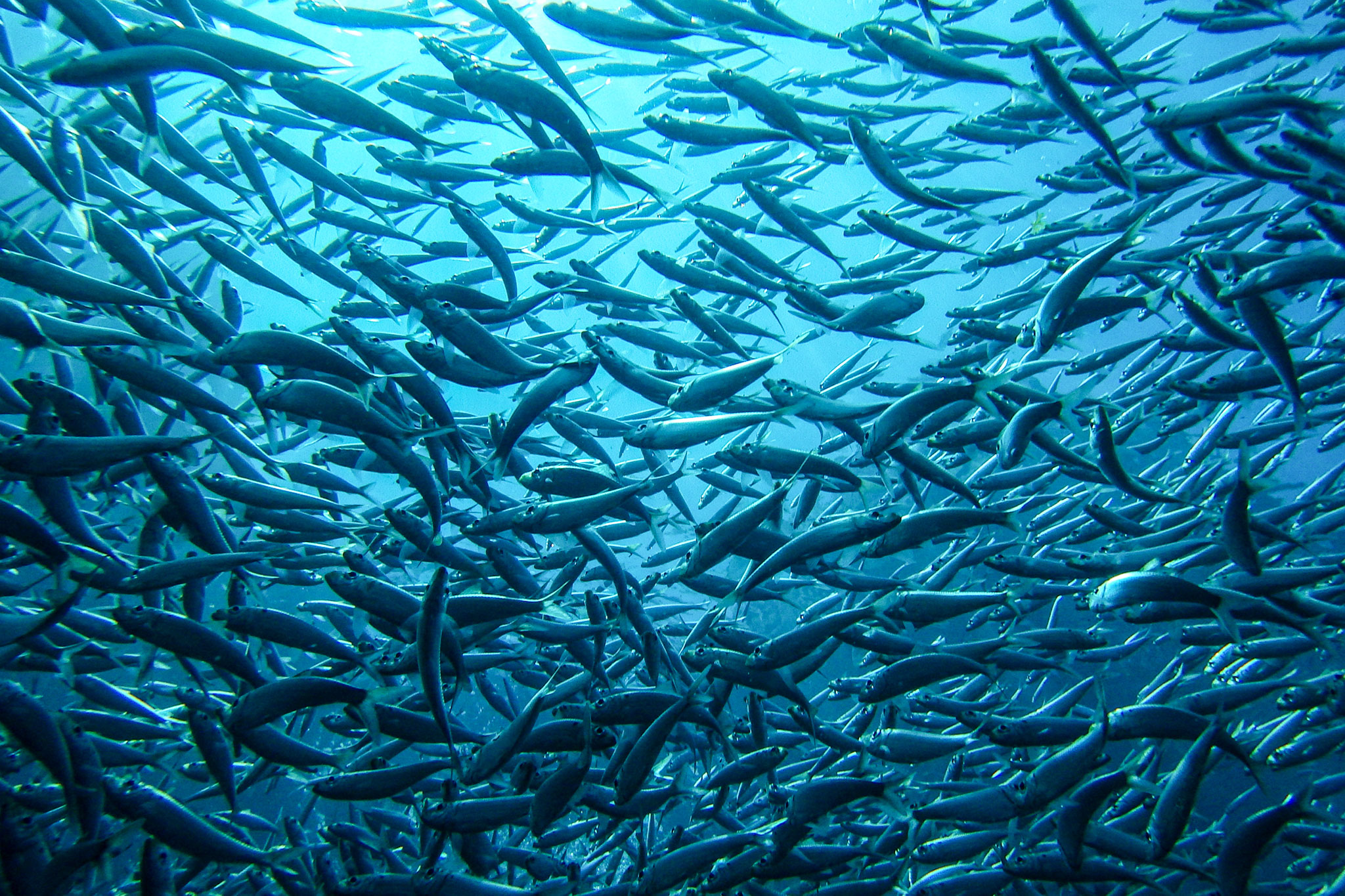

Most fish do not regulate their body temperature, instead, they live where the water temperature is ideal for their functioning. Tunas are an exception to this because they regulate their body temperature, regardless of the water temperature. This form of metabolism raises the body temperature by burning calories through muscular exercise: swimming. Tunas travel in schools of fast and hungry fish, and can go back and forth after their favorite preys, sardines and anchovies, in the cool waters of Japan and North America, and the warm waters of Baja California Sur and the Taipei Sea.

As you can imagine, this predator-prey ratio is highly demanding in terms of energy: to increase the weight of a tuna by 1 kilogram, it is necessary for it to consume 10 kilograms of sardine, because most of the intake is burnt swimming after sardines, which in return burn 90% of their plankton intake escaping tunas.

Moving to land, the story gets complicated. The Pacific bluefin tuna (BFT) has been in the Japanese diet for hundreds of generations. It is part of the country’s culture and tradition, and it has a special place at the Tokyo market. Today, this tradition is available to millions of people thanks to the dispersion of sushi and sashimi to all the big cities in the world. Most of the BFT is sold in auctions at the Tsukiji Fish Market in Tokyo, where all the fish that get there are sold in advance just to fix the price. In 2013, a 221-kilogram BFT specimen was sold at a record price of $1.76 million dollars. And here is where things get even more complicated, because the demand for an overexploited population keeps growing, and we have not allowed any time for it to recover.

The bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) is born on the shallow Asian coasts, between Philippines and Japan. It remains a couple of years close to the land, and it is there where it has been fished traditionally, by hand, using a fishing line and a hook. This fishing effort provides protein to millions of people, and it is at the same time the one that predates the most specimens, because all of them are young, less than three years old.

Those who manage to escape the fishing lines and hooks, start their journey to the open sea in search for food, some young specimens migrate to the coasts of the United States and Mexico to spend two or three years hunting and gaining weight, to then return to Asia to breed. This is if they make it through the purse seines, which catch entire schools of tuna around the Pacific —including their migratory route— and the waters of the Mexican Exclusive Economic Zone.

The fisheries’ managers calculate the size of a population through its volume in tons (biomass) and they call it stock or product. This figure is obtained by measuring the ratio between the fishing effort (how many fishing hours) and the caught tons, this is all calculated with a product vision, not a wildlife vision. The difference is not just semantic, it has implications in terms of environmental services. Fish in the sea, besides being the target of the fishing industry, are key elements of the ecosystem and provide services within the trophic chain that connects the continents.

The estimated size of the population of the BFT in 1952 was 145,000 tons, reaching its peak at 215,000 tons in the 60s. It is currently estimated to be less than 40,000 tons. According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the species is on the Red List of threatened species, under the vulnerable category, and the Union considers that its population is overexploited, and that overfishing is still happening.

The catch volume for industrial fishing started being measured in the 1950s, and in 1956 it hit a record 40,000 tons. Even though the fishing effort has kept going up since then, and new high technology has been incorporated (helicopters, 3D detectors, seine purses kilometers long and 500 meters depth, fishing boats with capacity to catch and freeze 800 tons in a single trip etc), the catch continues to go down. Bad sign which indicates the constant reduction of the population.

In 2008 24,507 tons were caught in the Pacific, and in 2014, just 17,065 tons. 81% of the capture occurs in Asia (Japan, 93%, South Korea, 5% and Chinese Taipei, 2%) and the remaining 19% of the fishing occurs in North American coasts. Out of the fishing that takes place in North America, 83% is caught by the Mexican boats (purse seiners /farming for exports) and 17% by American boats (mainly sports fishing).

In Mexico, the BFT industry uses a combined approach for the management of tunas, it captures live specimens in waters of the Exclusive Economic Zone and slowly transports them to big floating farms off the shores of Ensenada, Baja California: tuna farms. These facilities are anchored to the sea bottom, and are generally located near the coast for easier surveillance, transport and management of all other operations. The objective of the farm is to increase the weight and size of the specimens over a period of three to eight months. Cheap food is used for this process, and it is mostly frozen sardines.

Farms are located close to the shores, in shallow waters, therefore the natural dispersion of biological extrusions the tunas is not optimal, and great quantities of organic nitrogen accumulate in the surrounding sea bottom, particularly downstream. This accumulation could have grave consequences for the biodiversity of the area, and if it persists with no rest intervals, the damage could be long lasting.

According to data the Department Agriculture, Resources and Fishing, the BFT market in Mexico is dominated by six companies, all of them based in Baja California. Most of the farmed tuna is exported to Japan through Japanese brokers. In 2006, the income generated for the 4 350 tons of tuna produced in our country was 74 million dollars, but these were sold for 714 million dollars to commercial intermediaries in Japan.

What can we do about this? As a country, we should involve the environmental sector and a variety of academic views to make decisions concerning the handling of the species, prioritizing conservation and sustainability based on scientific evidence. We could even propose restrictive measures for commerce, through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

As individuals, we must demand to our authorities responsible management of our resources, based on science and prioritizing conservation over exploitation, and stop consuming bluefin tuna and other unsustainable marine products such as industrial shrimp or farm salmon.

About the author

He has more than 20 years experience in diagnosis, planning and application of initiatives related to the conservation of natural resources and sustainability. For 10 years, he was Associated Director for The Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve (Baja California Sur), where he developed different programs, the following stand out: protection of the gray whale, environmental education, management of the fishing activities within the protected area, recovery of threatened species and sustainable exploitation of the wildlife of the region. He collaborates with Beta Diversidad and has run conservation and sustainable management programs in Oaxaca, Veracruz, and Campeche (in Mexico).